Jemapela Photography

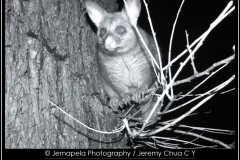

Most people who do infrared (IR) photography might be unaware that it can also be used for covert night time photography, such as for wildlife or surveillance. Many CCTV security cameras are designed to be IR sensitive, and used together with IR illumination which is almost invisible to human eyes, can record photos and videos at night.

In late 2012 to early 2013, I modified a Canon PowerShot SX20IS to be IR sensitive, and also modified its built-in flash to emit IR. I also modified a small LED lamp by replacing its white light LEDs with specially selected IR light LEDs. Together with this small modified LED lamp, I used the camera to photograph Australian wildlife, the common possums, at a public park in Melbourne CBD.

The following gallery contains images of the possums photographed at night, and the Canon PowerShot SX20IS and LED lamp dismantled in its modification process.

A few months later in 2013, I photographed possums again at night with a modified Canon PowerShot G9 and modified a bigger LED lamp.

My work at Camera Clinic as a camera technician not only has me repairing digital SLR cameras but sometimes also modifying them for special applications such as infrared (IR) photography.

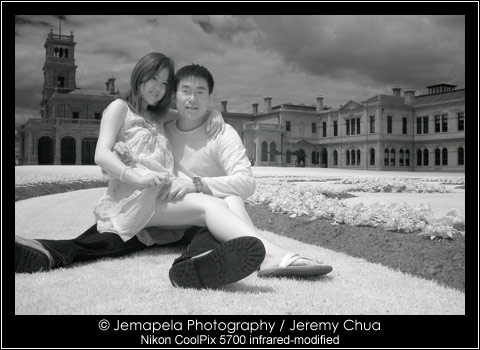

Although my interest in photography is primarily in portraits, I also have some interest in infrared (IR) photography. With IR-converted digital cameras, it is possible to shoot IR portrait images without the hassle of very long exposure times and the inconvenient use of a tripod.

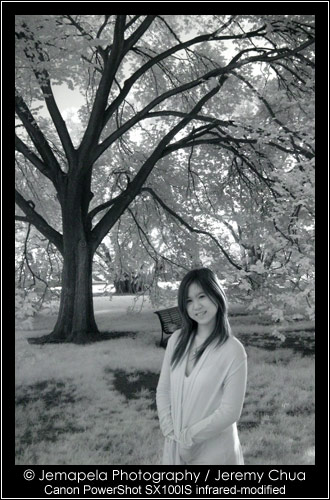

These are some simple IR portraits I shot in 2009 using an IR-converted Nikon CoolPix 5700 and an IR-converted Canon PowerShot SX100IS camera. I modified both these cameras and also several other cameras at my workplace Camera Clinic.

Infrared image of Averal and I.

Infrared close-up image of dark brown Asian eyes.

Infrared portrait image.

As interest in infrared (IR) photography grew, I did more IR conversions on digital cameras at Camera Clinic. In October 2010, I did about 10 IR conversions mostly on digital SLR cameras.

Using an IR-converted and focus corrected Canon EOS 5D Mark II with Canon EF 17-35mm f/2.8L USM and Canon EF 85mm f/1.8 USM lenses, I shot a few infrared portrait images in RAW+JPEG formats. I also used the IR-converted Canon EOS 5D Mark II to record IR videos. Shot with custom white balance, these images shown are the JPEG images out-of-camera and have not been digitally manipulated or enhanced.

Infrared portrait using an infrared converted Canon EOS 5D Mark II.

Infrared portrait using an infrared converted Canon EOS 5D Mark II.

Contrary to popular theory or belief, IR-converted digital cameras are not completely free from the hot spot problem that is very common with unconverted digital cameras. Through my experience converting digital cameras and testing them with several lenses, faint hot spots can still occur with a very few lenses.

Unlike normal photography, infrared (IR) photography usually does not contain much colour. Ideally the photographer should do a custom white balance of the scene when using an IR-converted digital camera because automatic white balance often results in images that have a reddish or purplish colour cast. It is usually considered correct to do a custom white balance by measuring white balance on green grass/leaves on a sunny day. This white balance measurement renders the IR image looking similar to black and white images.

If custom white balance was measured on something else, say blue sky or red brick, the resulting IR image may contain some rather strange colours. This colour is called “false colours”, and some photographers like it. Predicting the occurrence of false colours is difficult because it varies between digital camera models. Based on research and experience, some digital cameras do not produce false colours. The appearance of false colours also depends on how the custom white balance was done.

In June 2010, I shot some IR images using an unconverted Canon PowerShot A650IS with a Hoya R72 filter held in front of the lens, and was surprised to observe that it does not produce the hot spot flare in its images. Its smaller brothers, the A630 and A640, also do not produce the hot spot flare when shooting IR images.

In July 2010, I shot more IR images using my specially-modified Canon PowerShot SX120IS with a 680nm infrared filter. Shot at Mount Buller and at Echuca, it was at Echuca that I discovered the custom white balance I did using a 950nm infrared filter tended to produce a sepia-tone appearance in images shot with a 680nm filter.

Some of the images shown were not post-processed, but some have been enhanced to improve visual appearance.

Very few digital cameras are manufactured to be compatible for infrared (IR) photography, and the biggest blame for this incompatibility probably goes to lenses. Many lenses are not able to capture IR images without causing the annoying hot spot in the center of IR images. Usually appearing as a whitish or reddish circular patch, hot spots are always more prominent when using smaller apertures, and less visible or even absent when using bigger apertures.

Generally, the occurrence of hot spots can be greatly reduced, if not totally eliminated, by converting (modifying) the digital camera for IR photography.

In the following gallery of images, it is observed that the unconverted Fujifilm FinePix S6500fd produces hot spots.

In April 2010, I repaired a dead Canon PowerShot A640 camera to test its capability for infrared photography. Together with this revived unconverted Canon camera, I also tested an unconverted Canon PowerShot SX120IS and an unconverted Fujifilm FinePix S6500fd with the ever popular Hoya R72 filter.

In March 2010, I bought a Canon PowerShot SX120IS camera specifically for spectral modification. With compliments from my boss at Camera Clinic who provided me with a Wratten 89b equivalent polyester filter, I dismantled the camera, cleaned dust off the filter as best as possible, fitted the filter, and set down the imager sensor to a height for correct focus. The camera is now infrared converted and is now able to see infrared from about 730nm and higher.

I used this infrared converted camera during my Good Friday Easter Sunday super long weekend road trip to Port Campbell National Park, Warrnambool and Port Fairy.

Digital camera infrared (IR) photography can be done generally in 2 ways. The cheap but inconvenient way is to attach an IR-passing filter, such as the popular Hoya R72, over the lens and shoot images. The expensive but convenient way is to have the digital camera converted and calibrated for IR photography.

The cheap inconvenient method is slow and clumsy, and it is not always a sure-fire way of producing IR images. This method can sometimes produce a whitish circular flare in the center of the IR image, often called a hot-spot. This hot-spot becomes more visible with images shot at small apertures, and it can be observed that the hot-spot bears the shape of the diaphragm opening. There is no easy remedy for this optical problem.

The expensive convenient method is fast and easy. Not only are hot-spots absent, exposure times are short enough for hand-held photography. Not only can the tripod be left at home, the modified camera can be used at lower ISO values hence producing images with lesser electronic noise and higher clarity, or used at smaller apertures for longer depth-of-field to complement landscape photography which IR photography is popularly used for.

The conversion or modification of a digital camera for IR photography requires careful disassembly by a qualified technician, and sometimes the camera has to be optically (focus) calibrated after the modification. The imaging sensor (focal plane) position and lens focus (autofocus shift) can be calibrated to suit IR transmission in the camera-lens system. This calibration is necessary for the camera to correctly focus IR wavelengths and hence produce sharply focused images.

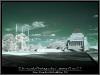

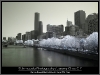

The following gallery presents infrared images I photographed in December 2009. Photographed in Sydney CBD, Royal National Park, Sea Cliff Bridge (Grand Pacific Drive), and Hunter Valley wine region, these IR images were appropriately enhanced in Adobe Photoshop for an improved visual appearance. I thank my Burmese friend Pyay Phyo Kyaw for hosting me in Sydney.

The Canon PowerShot SX100IS camera was infrared-converted by me in my workplace at Camera Clinic.

The human eye can see light and its reflected colours of a limited range. Generally, we call this the visible light spectrum, and this light has wavelengths from 380nm to 750nm. Beyond this range, that is, wavelengths below 380nm (ultraviolet) and above 750nm (infrared), the light is invisible to humans. Some insects and animals can see beyond the visible light spectrum.

Infrared (IR) photography is the formation of images with light at wavelengths above 750nm. In reality, most IR photography is actually the capture of near-infrared (NIR) light of wavelengths up to 1300nm, or in simpler words, the lower end of the infrared range. However, most people simply use the term “IR” or “infrared”.

Near-infrared photography can be done using most digital cameras. The CCD/CMOS imagers in most digital cameras can “see” near-infrared (NIR) light, but it is blocked away by an IR-block filter. This IR-block filter is often a clear or bluish-tint glass fitted on top of the imager.

For simplicity in explanation, generally NIR images can be photographed with a digital camera using an IR-pass filter attached in front of the lens. It is much better if the IR-block filter inside the camera is removed and an IR-pass filter is fitted on top of the imager, but this requires dismantling the camera.

Dismantling to repair or modify a digital camera should only be done by a qualified, trained and experienced technician. Electric shock, personal injury and damage can occur if a camera is dismantled by an unqualified person.

Although my interest in photography is primarily in portraits, I also have some interest in infrared photography. At my workplace in Camera Clinic, I have converted a few digital cameras to do infrared photography.

Some of the digital cameras I have converted for infrared include:

Nikon D1, D70, D200

Nikon CoolPix 5700

Canon EOS 10D, EOS 20D

Canon PowerShot G10, PowerShot SX100IS

The following gallery presents infrared images I photographed in 2007 and 2009. These images have been appropriately enhanced in Adobe Photoshop for an improved visual appearance.

The Nikon D50, Nikon CoolPix 5700 and Fuji FinePix S20 Pro used to shoot the above images were modified at my workplace Camera Clinic.